The author with Prince Hassan bin Talal in Amman, 2009 – Photo from the book

The author with Prince Hassan bin Talal in Amman, 2009 – Photo from the book

On page 88 of this extraordinary book, while recalling his family’s migration from Hyderabad Deccan in India to Pakistan in 1949, the author digresses briefly. He writes: “ … the topsy-turvy way in which I have written this book and, in that process, played havoc with chronology … ”. But for this reviewer at least no regrets are required. A stream-of-consciousness dimension sometimes marks the narrative. The text moves smoothly, sometimes abruptly from one time zone to another, even from one subject to another within a single chapter or section. This unpredictable mobility is precisely one of the several qualities that make Muhammad Ali Siddiqi’s book refreshingly different from a conventional approach to sequentiality. There are pleasant surprises every so often.

Liberated from the long-observed limitations of word-counts for editorials, the author celebrates a new freedom of  expression with abundance that is appropriate, never excessive. Where editorials and sometimes even articles require an institutional, impersonal view, a forthrightly autobiographical approach enables the writer to be intensely personal, subjective, emotional and passionate about the ideas and people and elements he holds dear. Be it his attachment to, and despair about, Karachi, be it his profound devotion to the land of Pakistan, be they his ingrained progressive political and cultural perspectives, or his travels and sojourns in the UK, US and some Arab countries, the author writes with engaging vitality.

expression with abundance that is appropriate, never excessive. Where editorials and sometimes even articles require an institutional, impersonal view, a forthrightly autobiographical approach enables the writer to be intensely personal, subjective, emotional and passionate about the ideas and people and elements he holds dear. Be it his attachment to, and despair about, Karachi, be it his profound devotion to the land of Pakistan, be they his ingrained progressive political and cultural perspectives, or his travels and sojourns in the UK, US and some Arab countries, the author writes with engaging vitality.

Inexplicably there was a gap of five years between the writing, presumably completed in 2010, and the book’s publication at the end of 2015. There is a too-brief four-page postscript which seeks to fill the gap. Yet the lapse of time does not age the text. The 17 chapters remain as timely today as when they were written. Chapter titles do not necessarily convey the range of subjects or periods covered by each because of the shifts in space and time previously referred to. From his unlikely beginnings as a humble typist in non-journalistic jobs, to reaching the top of journalistic excellence in Pakistan’s finest English newspaper, these memoirs become, by turn, a high-speed roller-coaster ride, a relaxed time-machine travel trip, and a bracing excursion in an open motor-boat heading into the wind of change on choppy, rolling waves.

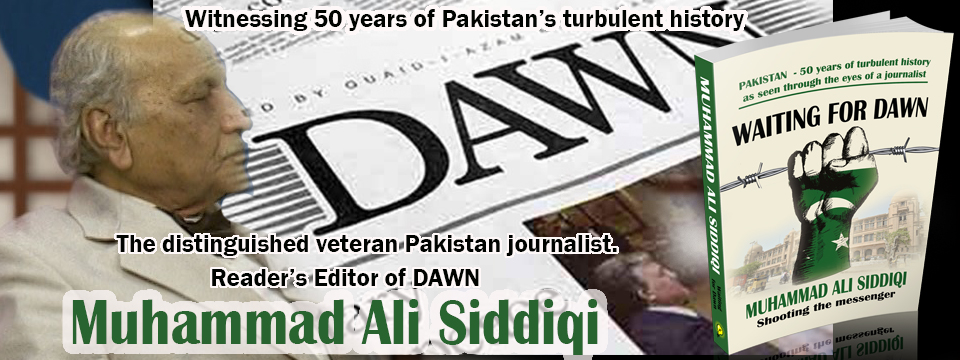

Muhammad Ali Siddiqi’s memoirs show his immense fervour for his country and his profession

Stormy and tumultuous though be the times the country and the writer have faced, torn by a loss of confidence in oneself and the nation as some have been, the author’s own sense of identity has remained rock- solid. In the third chapter ‘Revanche!’ he movingly recalls his arrival at Keamari Harbour on an afternoon in June 1949 to gain his first glimpse of his new homeland. Despite his deep attachment to the rich legacy of Hyderabad Deccan’s syncretic culture, he was enraptured at first sight. He writes, “ … the passing decades have only tended to reinforce my child’s love for Pakistan. For me, everything belonging to Pakistan is sacred … those who do not regard Pakistan as sacred: would they kindly leave it?” Rooted in this fusion of soil and soul, the author surveys a wide range of subjects to produce a testament to his unique country’s resilience and the humble patriotism of its citizens, whether they be ancestrally linked to this land or migrants.

The first part of the book’s subtitle From Religion to Fascism implies regression. It is possibly meant to reflect the decline from the promise of the original Pakistan to the betrayal of that pledge as apparent in our present condition. Yet, with due respect, religion is non-fascistic mainly or only when it remains a private bond between the faith and the individual. Which is rarely so, even in societies that claim to be secular: they often demand conformism to majoritarian practices.

Through most, if not all of Islam’s history, religion has always been interpreted as possessing a public institutional role with the holy right and authority to enforce compliance. This imbues religion with an inherently coercive facet, bringing it uncomfortably close to fascism. While the creation of Pakistan was fortuitous, if not miraculous, the emergence of religious authoritarianism was largely inevitable, given the failure to firmly set clear ideological directions at its inception. The author pulls no punches in articulating his continuing disquiet on the long, dark, still-lingering shadow cast by Ziaul Haq’s blatant misuse of religion to pursue his personal lust for power.

“During my stay in Washington as Dawn’s correspondent, Benazir Bhutto visited America twice, first as leader of the opposition in the summer of 1993 and later as prime minister in March-April 1995. The last time she had visited America was in June 1989, when she took the country by storm, for she had come to America after years of jail, five of them in solitary confinement, where Zia’s agents tried to plant in her mind the idea of suicide (Benazir Bhutto: Daughter of the East). More important, she had made history by becoming the first woman to be the prime minister of a Muslim country. Her struggle was titanic, for she had stood up against a military dictator and parties that believed in physically eliminating the Bhutto family; a process that ended ultimately with her assassination on Dec 27, 2007. Between June 5 and 10, 1989, Benazir made on the American leaders, people and media an impression that few non-Western leaders had made. Here was a Muslim woman, charismatic, Western-educated and endowed with courage and brilliance, demolishing the Muslim woman’s stereotype image painted by the American media. Even though the Soviets were winding up in Afghanistan, the Pressler Amendment was still on and aid to Pakistan still continued. On June 6, president George Bush Senior and Benazir watched as Pakistani and American officials signed a series of agreements worth nearly half a billion dollars, including $565m for economic development and $1.5m for eradicating drug trafficking.” — Excerpt from the book

Siddiqi’s boundless faith in Pakistan, its land and its people as articulated at several points throughout the book belie the regressive implications of the first part of the subtitle. This is one veteran journalist who has not been infected by the occupational disease of cynicism. On a conceptual level and on a nostalgic level, he is inextricably bonded to his country, his memories and his hopes. He relishes the simple delights of tea and snacks in an Irani restaurant of yesterday’s Karachi. He recalls the magic of his addiction to English movies (with The Night of the Generals and The Guns of Navaronebeing favourites). He laments the disappearance of the Karachi of the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s. He celebrates the country’s capacity to produce the Muslim world’s first female prime minister. He forcefully reiterates that he is a Pakistani first and last. He affirms pleasure in the little things that make life special in Pakistan and thoughtful concern at the larger challenges that confront the country.

The second part of the subtitle is certainly accurate in that the book records a distinguished journalist’s professional life. But there is far more to the text than material restricted to one person or one profession. The author dwells on the geopolitical landscape of the past 40 years in particular. He also delves informatively into aspects of Middle Eastern and South Asian history. His analysis of diverse issues is incisive, sometimes scorchingly honest, always striving to be truthful. The subjects covered include the left’s stagnation and decline, the hypocrisy and obduracy of the religious right, the brave aims and failures of trade unionism, especially among journalists, the brutality of Zia’s martial law, the congenital hostility of Indian governments towards Pakistan, the harsh reality and the myth-making about British colonialism, and the vagaries of American foreign policy. Of particular value is the chapter ‘Brother Arabs’ in which he demolishes major misconceptions nursed by some Pakistanis and stresses the need to reconstruct our perceptions about the Arab psyche.

Siddiqi’s evolution as a journalist par excellence included phases of detachment from Dawn when he worked with Morning News and with The Sun, both now extant. He candidly and admiringly recalls how the editor Ahmad Ali Khan guided and nurtured his career, how several other colleagues inspired him with their own sincerity and professional skills, and how others who were not in the same newspaper nevertheless served as sources of learning and guidance.

While the book comes as an apt companion text to Ahmad Ali Khan’s notable, posthumously published autobiography In Search of Sense (2015), Siddiqi’s view of Dawn is possibly the most informative and revealing insider’s account of a leading newspaper’s internal life. His recounting brief tenures in non-journalistic employment, such as in a US military group’s office in Karachi, provides amusing moments and diversions. Such recollections also typify the absorbing directness with which he remembers how he and his family coped with meagre incomes for several years. Enjoying bus rides across the city, attaining university education, coping with the family’s needs before buying his first car: such passages resonate with endearing honesty.

Siddiqi also recalls his visits to the UK on a Thomson Foundation fellowship and his tenure as Dawn’s correspondent in Washington D.C. Tongue-in-cheek, he calls the UK “a hot country.” His descriptions of the views from his bedroom in Wales or the empty, soulless streets of the American capital aptly capture the aura of the places, and the loneliness. Yet, at the same time, he notes the methodical, disciplined order that shapes Western societies and cities. His reportage of Pakistan’s presence in Washington D.C., through Syeda Abida Hussain’s eventful ambassadorial tenure or prime minister Benazir Bhutto’s impactful meeting with president Clinton in 1995 is sharply observed and perceptive.

Of a few small quibbles, only one needs to be cited. It is curious that there is a coincidence here. Both Ahmad Ali Khan in his book, and Siddiqi in this book, incorrectly credit prime minister Muhammad Khan Junejo (1985-1988) for lifting restrictions on the press. While Junejo certainly showed unusual tolerance for criticism, the formal repeal of the repressive law, known as the Press and Publications Ordinance promulgated by president Ayub Khan actually took place during the interim government headed by president Ghulam Ishaq Khan in September 1988. But minor distractions should not prevent this book from being read by all journalists, all citizens interested in learning, and all political leaders and government officials, especially those concerned with information and the media.

The reviewer is a member, Senate Forum for Policy Research, and a former federal minister of information, and former senator.